A Large Catholic Parish and a Tiny Synagogue Build Bridges Upon Italian Religious Diversity of Understanding In the “Toe” of the Italian “Boot!”

The knock at the door was so soft that I almost ignored it. After all, the wind had been blowing hard in our mountain village and the sound I heard might have been a rogue branch battering a window or a wall.

The door, like the entire house, is hundreds of years old, made of solid chestnut at a time when the Jews who founded our village often feared for their safety. They hid behind thick walls and locked wooden doors – the same door I now stood behind, wondering if there was someone outside. Then when I heard the knock again, I opened the door.

He stood before me, tall, thin and young. The wind was blowing his longish hair into a tumbled mess and when he noticed that he still held a cigarette in his hand his faced reddened in embarrassment. “No problem,” I said, not wanting to create any more discomfort for this young man who was obviously ill at ease. And with that, he smiled and extended his hand. “You are the rabbi,” he said. “I must speak with you.”

That is how I met young Luca, a nineteen year old young man whose grandfather had recently passed away. Over a hearty espresso Luca spoke about his “Nonno” with great admiration. I listened politely and as I wondered what exactly brought Luca to my door, when suddenly this nervous young man began his explanation.

“My Nonno was a wonderful grandfather. When I was a little boy he took me everywhere and on every journey he told me stories of our family. How we once lived in Spain and how we had moved from one place to another. Nonno said we were from a strong and special group. What group? He never would say. Not until he lay dying. He motioned me close to his bed and asked that I open the drawer to his desk. I felt inside and found this!”

At this point Luca carefully placed his treasured item on my kitchen table. I recognized at onc e that this long thin pointer was a Jewish ritual item. A pointer like this one, with a little hand at one end is called a “yad” (the Hebrew word for “hand”). A yad like this one was once used to read the sacred Torah scroll – the most important of all things Jewish.

e that this long thin pointer was a Jewish ritual item. A pointer like this one, with a little hand at one end is called a “yad” (the Hebrew word for “hand”). A yad like this one was once used to read the sacred Torah scroll – the most important of all things Jewish.

“Nonno said that if I ever met a rabbi I should bring this thing to him (he blushed again) or her. He said that a rabbi would tell me what this is.”

As I held the yad in my hand, I realized what had just happened. Jewish traditions long hidden had come to light and through a grandfather’s death bed admission, Luca was about to learn about his family’s hidden heritage.

Later I invited to Luca to join me in our synagogue, Ner Tamid del Sud. It is the first active synagogue in Calabria (in the deep south of Italy in an area the size of the US state of Virginia) and the first synagogue in 500 years since Inquisition times.

I took the Torah from its special cabinet (Aron Kodesh) and slowly I unrolled it on the reading table. I gave the precious yad to Lucca and then I guided his hand as he used his grandfather’s yad to touch the ancient Hebrew words on the scroll.

“This is your heritage,” I said to Luca. “Your grandfather wanted you to know that long ago your family was Jewish.”

Thanks to the United Nations Conference on Religious Pluralism, Tolerance and Italian Religious Diversity: The Bahrain Model, we have the opportunity to discuss this important issue and share individual experiences that support the Bahrain model – a system that promotes the idea that religious minorities can live cooperatively within a country’s religious majority. Luca’s story holds the key – especially when he explained how he found the courage to knock on my door.

“I was so afraid to speak about this,” Luca said. “I already had an idea that our family might have been Jewish but I was afraid. So I went to the priest. He knows our family well. Some of us have been Catholic for generations but Don Gigi told me that I should talk to you.”

Don Gigi Iulianois the parish priest of our village, Serrastretta. He has been the spiritual leader of the hundreds of Catholics for nearly two decades. Don Gigi represents the majority religion – Catholicism – but together we have found a way to incorporate the principles of Religious Pluralism into our respective communities resulting in greater understanding and respect between us.

According to many experts, Religious Pluralism generally refers to the belief in two or more religious worldviews as being equally valid or acceptable. Religious Pluralism goes beyond tolerance in that those of us who practice it believe that there are multiple paths to God. Or, as Cantor Kate Judd of Hebrew Union College puts it, “ Let’s all live together in peace, knowing that no one (religion) has a corner on the truth!”

Diane Eck of the Pluralism Project at Harvard University emphasizes that there are four basic points that can guide our thinking. So let’s use our story of the young man, Luca, Don Gigi, the parish priest and my role as the synagogue rabbi to determine how it is possible to apply the principles of Religious Pluralism to real-life settings.

Principle 1: Ms. Eck explains that “pluralism is not diversity alone, but the energetic engagement with diversity.” Eck says that real diversity without person to person encounters and without relationship building will increase tension in society.

Diversity exists in our village. The majority are Catholic with a tiny minority of Jews who frequent our synagogue along with many who consider themselves secular. Within this climate Luca discovered his Jewish ancestry, and he began to understand that his background was different – diverse.

Yet by applying the tenets of Religious Pluralism, Don Gigi and I had been able to create a spiritual climate that allowed for personal engagement and relationship building between our two faith communities.

Our initial experiences included determining which of our respective holidays were biblically based, such as the Jewish holiday of Sukkot ( for Catholics, The Festival of Tabernacles) and the Jewish holiday of Shavuot (which for Catholics is related to the festival of Pentecost) and how we might celebrate together. Adults and students visited each other’s houses of worship. Jews visited the parish church and Catholics felt comfortable to enter the synagogue and both groups often joined together for cooperative study and cultural exchange .

Principle 2: “Pluralism is more than tolerance . Across lines of difference, Religious Pluralism actively seeks mutual understanding.” Dr. Eck goes on to explain that tolerance is a necessary public virtue but tolerance does not require that people of different religions specifically know about one another.

For Don Gigi and me, as priest and rabbi, we have learned that Religious Pluralism cannot exist in an environment of ignorance. For our little village it was not enough for our congregations to know that a synagogue was located two streets behind the church. As spiritual leaders we understood that our congregants needed to understand what happens behind our doors.

For this reason Don Gigi and I offered opportunities for our congregants to come together to study each other’s religion, to ask question and to share myths and misconceptions about our respective beliefs. Judaism is presented and discussed in Catholic confirmation classes and the Catholic traditions of our village are explained in our synagogue.

When Luca, our Catholic young man with the yad, approached the synagogue, he did so knowing that local Catholics had a history of positive experiences with our synagogue. He anticipated that the rabbi would welcome him.

Principle 3: Religious Pluralism “is not relativism.” Instead Religious Pluralism requires respect for individual religious identity. This principle was especially important for the Catholic majority and the Jewish minority in our village. Our identities are shaped in part by our religious beliefs, some of which have held historically that “my religion is better than yours.”

Don Gigi and I have participated in each other’s festivals and life cycle events and have encouraged our congregants to join us, all the while understanding that we are “guests at each other’s party.” We use the analogy of young children who are invited to a friend’s birthday celebration. The guests enjoy the food and the festivities but understand that the celebration is designed for someone else.

As a Catholic priest whose beliefs include the sacrament of baptism, Don Gigi attended a Jewish baby naming ceremony in our synagogue. The parish priest participated as a guest.

Later I was invited to visit the Catholic Church during Sunday mass. Although I do not embrace Catholic theology, I was delighted to read a selection from The Prophets, so that congregants could hear a portion of the Bible read in Hebrew, its original language.

In both instances Don Gigi and I modeled respect for each other’s festivals and rituals while acknowledging that our theological beliefs are basically very different.

Principle 4: Diane Eck puts it well when she says, “Religious Pluralism is based on dialogue.” She emphasizes that dialogue requires both speaking and listening and does not require that everyone always agree.

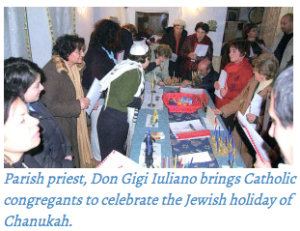

Don Gigi opened the dialogue of Religious Pluralism many years ago when he announced from the pulpit that he planned to accept my invitation to the synagogue to learn about and share in the celebration of Chanukah. Don Gigi told his congregation, “Because Chanukah is the festival that celebrates religious freedom, it seems entirely appropriate that we Catholics and Jews should celebrate together. I will accept the rabbi’s invitation and I hope that you will do so as well.”

Years later when Luca was given his grandfather’s yad and along with it, the gift of a Jewish identity, his first stop on this new spiritual journey was a visit to his parish priest. Because Don Gigi and I share a belief in Religious Pluralism, Luca was able to bring not only his yad, but his concerns to his Catholic religious leader who then encouraged him to speak with me – a rabbi that could shed light on Luca’s Jewish heritage.

Thanks to Religious Pluralism the young man in our story was not torn emotionally by his grandfather’s admission. Neither the priest nor the rabbi pressured Luca to forsake one belief or practice for another. Instead he was free to explore and study both religious traditions to determine how he might apply them to his own life.

Diane Eck writes that as far as Religious Pluralism is concerned, “everyone at the ‘table’ need not agree with one another. Instead coming to the ‘table’ with differences in hand is the basic commitment of Religious Pluralism. Encouraged by his priest, Luca came to the synagogue to share his family’s yad with a rabbi. Thanks to a commitment to Religious Pluralism, Luca was accepted and embraced by both faith communities. He was not forced to choose one faith community over the other. Instead both communities – Catholic and Jewish – extended the hand of friendship and acceptance and welcomed Luca home.

Rabbi Barbara Aiello was embraced by a select group of worldwide religious leaders on March 4th, 2016, when addressing the United Nations on Pluralistic Judaism.

Ms. Nancy Khedouri (right) Jewish member of Bahrain Parliament and featured speaker on the Religious Pluralism and Tolerance Bahrain Project, with Rabbi Barbara (left). Ms. Khedouri spoke passionately about her country’s initiative of religious tolerance and acceptance for all of Bahrain’s minority religious groups.

Rabbi Barbara Aiello with Shaikh Abdulla Bin Ahmed bin Abdulla Al Khalifa of Bahrain (left ) and Mr. Amin Abdel Latif. Shaikh Abdulla hosted Rabbi Barbara in a group of 12 presentors invited by Shaikh Abdulla. Rabbi Barbara was invited to speak about her work as an expert in Religious Pluralism and Tolerance in Calabria, Italy.